IPFS

What is the "Credit Freeze"?

Written by Brock Lorber Subject: Economy - Economics USAWith alarm bells still ringing about a “credit freeze” it seems as if taxpayers should know exactly what kind of credit they're being asked to un-freeze. Perhaps The Powers that Be are unwilling to offer a simple explanation is because the simple truth is far scarier than the “fire and brimstone raining down on Main Street” hyperbole: right now big banks do not want to loan to each other.

At the end of the day, the bank's books have to balance just like any other business. However, the bank has an additional ratio that has to balance whenever the teller windows are closed. Their cash and reserves (deposits with the Federal Reserve Bank) must be equal to or greater than some percentage of demand deposits with the bank.

While the reserve requirements are different for different types of deposits, we can simplify the explanation by saying, in the US, a bank's cash and reserves must equal 10% of deposits. For example, if a bank has customer demand deposits totaling $210 billion at the end of the day, it must have $21 billion in cash and reserves.

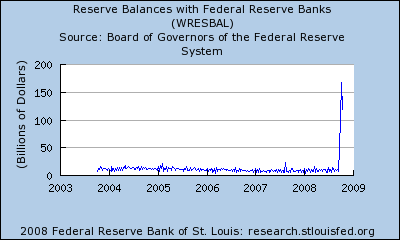

While banks are historically good at approximating their cash and reserve needs from day to day, they will, of course, be a little long or short of the 10% requirement on any given night. If a bank is short, they borrow reserves from other banks who have excess reserves that night. Over the next day or three, the borrowing bank will use incoming deposits or asset sales to pay back the loan. These overnight loans are facilitated by the Federal Reserve.

The rate of interest on these overnight loans is called the Fed Funds Rate. When you hear that the Fed has raised or lowered interest rates, this is normally the rate being referred to. It is important to note, however, that the rate set by the Fed is a target, not a set rate. While banks that are short on reserves must borrow, banks that are long do not have to lend. Therefore, the actual interest charged on an overnight loan may be higher than the Fed Funds target to entice banks with excess reserves to make interbank loans.

This is the “credit freeze” we've been hearing so much about. Strong banks have excess reserves to lend, they are just unwilling to lend to each other so these overnight loans have become very, very expensive. In other words, lending banks are calling out borrowing banks as being practically insolvent (all fractional reserve banks are technically insolvent).

And, who could blame them? In Washington Mutual's waning days, depositors had withdrawn almost $17 billion, depleting their reserves; as much of WaMu's assets consisted of mortgages that nobody wants to buy at current valuations, other banks were scared to lend their reserves to it. It doesn't make sense for a bank to lend to another bank that is depleting reserves and can't sell assets quickly to cover the loan.

Let that sink in. The nine largest

banks are being forced into a nationalization scheme, with all its

attendant problems. What chance does the Bank of Winemucca have

against state-owned banks who just happen to be the nine largest in

the country? (click on the picture at right to see Peter Schiff and Robert Poole discuss this nationalization with Glenn Beck)

Let that sink in. The nine largest

banks are being forced into a nationalization scheme, with all its

attendant problems. What chance does the Bank of Winemucca have

against state-owned banks who just happen to be the nine largest in

the country? (click on the picture at right to see Peter Schiff and Robert Poole discuss this nationalization with Glenn Beck)